Introduction

Cobras are among the most dangerous and feared venomous snake species in the world, belonging to the family Elapidae. They are predominantly found in tropical and subtropical regions, particularly across the south of Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa [1]. These environments provide the warm, humid conditions ideal for their survival and hunting behavior.

In fact, bites from cobras—particularly the Indian cobra (Naja naja), are among the leading causes of snakebite-related deaths in rural parts of South, Southeast Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa [2]. Once bitten, the venom—which contains potent neurotoxins—begins to act rapidly, interfering with the victim’s nervous system by blocking neuromuscular transmission. Without timely intervention, this can lead to progressive paralysis, respiratory failure, and eventually death.

What is cobra venom made up of

The venom of the king cobra, secreted by the postorbital venom glands, is mainly composed of three-finger toxins (3FTxs) and snake venom metalloproteinases (SVMPs) [3-4]. The most prominent of these include the following-

1. Neurotoxins

- Block acetylcholine receptors at neuromuscular junctions.

- Causes muscle paralysis, including the diaphragm that can lead to respiratory failure.

2. Cytotoxins (including cardiotoxins)

- Directly damage cell membranes, leading to cell lysis (rupture).

- Often cause local tissue necrosis and organ damage.

3. Phospholipases A₂ (PLA₂)

- Enzymes that break down phospholipids in cell membranes.

- Promote inflammation, hemolysis (rupture of red blood cells), and tissue destruction.

4. Metalloproteinases & Hyaluronidases

- Degrade extracellular matrix components, increasing venom spread through tissues.

- Cause hemorrhage and swelling.

Cardiotoxins: A closer look

Let’s take a closer look into one of these venom components: cardiotoxins.

Snake cardiotoxins are a group of non-enzymatic, cytotoxic polypeptides that are a key component of cobra venom but also present in other snake species, such as kraits (Bungarus species) [5]. These toxins specifically affect the heart muscle (cardiomyocytes), leading to cardiac dysfunction, including arrhythmias, contractile failure, and sometimes cardiac arrest.

Snake cardiotoxins (CTXs) exert their effects primarily via direct interaction with the plasma membranes of heart cells. One of the methods that CTXs use is membrane insertion- cardiotoxins bind to and insert into the phospholipid bilayer, especially targeting negatively charged lipids like cardiolipin or phosphatidylserine. Another mechanism is membrane disruption, whereby they destabilize the membrane by forming non-specific pores or causing lipid phase separation, leading to increased permeability. Cardiotoxins can also penetrate cells and affect mitochondrial function, leading to depolarization of the mitochondrial membrane potential, release of cytochrome c, and induction of apoptosis or necrosis. Finally, cardiotoxins can also disturb ion gradients across membranes which in turn contributes to arrhythmias or cardiac arrest.

Cardiotoxin V

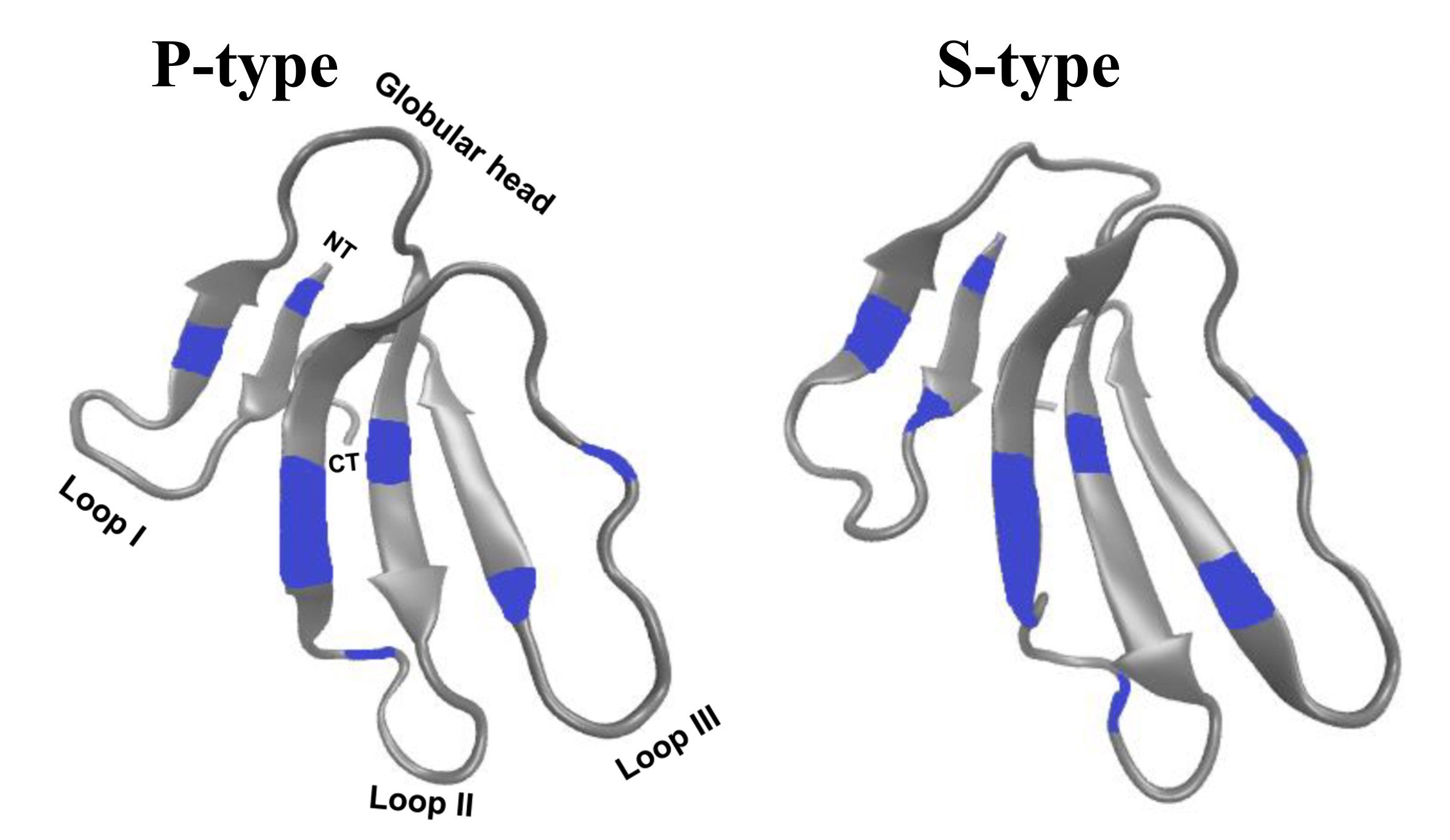

There are two distinct types of CTXs - the P-type and S-type, which can be distinguished by the presence of Pro31 and Ser29, respectively, near the tip of loop II. P-type CTXs exhibit stronger interactions with membranes compared to S-type CTXs; however, the specific structural and functional contributions of these two different types of CTXs are yet to be clarified.

Cardiotoxin V from Taiwan cobra (CTX A5) is a P-type CTX. It can cause vesicle aggregation/fusion around the phospholipid transition temperatures. CTX A5 possesses the characteristic three-finger motif and overall molecular structure typical of other snake toxins, including neurotoxins. The three-finger motif of CTX A5 is a well-documented characteristic of snake toxins, comprising a compact β-sheet-rich core and three extended β-strand loops, held together by disulphide bridges, extending from this core.

Unlike neurotoxins (which target receptors), cardiotoxins act non-specifically by integrating into lipid bilayers. Analysis of the crystal packing suggests that hydrophobic interactions, resembling those found in membrane bilayers, may contribute to the formation of the water-binding loop. The newly discovered continuous hydrophobic column formed by the three-finger loops may function as a lipid-binding site and potentially penetrate membrane bilayers through multimer formation within cell membranes. Similar continuous hydrophobic stretches, as seen in the helical and β-barrel structures of the photosynthetic reaction center and porin, are typically recognized as membrane-spanning segments.

The structure of CTX A5 determined at pH 8.5 offers insight into the pH-dependent membrane-associated activity of the molecule (PDB ID: 1CXI) [7]. The imidazole ring of His4 undergoes significant reorientation at different pH. Coordinated motion of other amino acid side chains near His4 have also been observed, indicating that local conformational changes associated with His4 protonation may contribute to the pH-dependent membrane-binding ability of CTX A5.

Figure 2. The structure of cardiotoxin V (CTX A5) from cobra (Naja naja) venom, solved using X-ray crystallography at pH 8.5 (PDB ID: 1CXI).

How does the anti-venom act

Broad-spectrum antivenoms against king cobra venom are available and may offer partial protection. These antivenoms are polyclonal antibodies raised in horses or sheep, targeting a range of venom components (neurotoxins, cytotoxins, etc.), including some cardiotoxins, but neutralization is not always complete. Antivenom efficacy against cardiotoxins is limited because:

- Cardiotoxins rapidly bind to cell membranes.

- Once bound, they are less accessible to circulating antibodies.

- Most antivenom formulations are optimized to neutralize neurotoxins, which are more acutely lethal.

Experimental studies in animals have shown partial neutralization of CTX-induced toxicity when antivenom is administered early.

Future research

The future directions of research on three finger toxins, such as CTXs from snake venom, spans across several fields, including drug development, structural biology and anti-venom innovation.

Currently, existing antivenoms are polyclonal and often fail to neutralize low-molecular-weight toxins like 3FTxs effectively. Therefore, some of the most exciting avenues of research include producing recombinant antivenoms using humanized or monoclonal antibodies or synthetic antibody libraries (phage display, yeast display). Using aptamers or small molecules to block toxin-receptor or toxin-membrane interactions is another promising approach.

Besides anti-venom properties, some of the three-finger toxins show selective toxicity to cancer cells or pathogenic microbes due to differences in membrane composition. The stable three-finger fold is also a promising protein scaffold for peptide drug design and targeted delivery systems.

About the artwork

Ziyun Zhou, a Year-10 student from the Tsing Hua Dao Xiang Lake International School in China was inspired by the proteins in Chinese Cobra venom that inhibit nerve activity, thus numbing the targets of their attacks. To create the artwork, Ziyun used familiar and opaque watercolors and acrylic markers.

References

- Stuart, B.; Wogan, G.; Grismer, L.; Auliya, M.; Inger, R.F.; Lilley, R.; Chan-Ard, T.; Thy, N.; Nguyen, T.Q.; Srinivasulu, C.; Jelić, D. (2012). "Ophiophagus hannah". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012: e.T177540A1491874.

- Pintor AF, Ray N, Longbottom J, Bravo-Vega CA, Yousefi M, Murray KA, Ediriweera DS, Diggle PJ. Addressing the global snakebite crisis with geo-spatial analyses–Recent advances and future direction. Toxicon: X. 2021 Sep 1;11:100076.

- Li, J.; Zhang, H.; Liu, J.; Xu, K. (2006). "Novel genes encoding six kinds of three-finger toxins in Ophiophagus hannah (king cobra) and function characterization of two recombinant long-chain neurotoxins". Biochemical Journal. 398 (2): 233–342. doi:10.1042/BJ20060004

- Roy, A.; Zhou, X.; Chong, M. Z.; d'Hoedt, D.; Foo, C. S.; Rajagopalan, N.; Nirthanan, S.; Bertrand, D.; Sivaraman, J.; Kini, R. M. (2010). "Structural and Functional Characterization of a Novel Homodimeric Three-finger Neurotoxin from the Venom of Ophiophagus hannah (King Cobra)". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 285 (11): 8302–8315.

- Teng, Che-Ming, Wentse Jy, and Chaoho Ouyang. "Cardiotoxin from Naja naja atra snake venom: a potentiator of platelet aggregation." Toxicon 22.3 (1984): 463-470.

- Gorai, B., Karthikeyan, M. & Sivaraman, T. Putative membrane lytic sites of P-type and S-type cardiotoxins from snake venoms as probed by all-atom molecular dynamics simulations. J Mol Model 22, 238 (2016). doi: 10.1007/s00894-016-3113-y

- Sun, Yuh-Ju, et al. "Crystal structure of cardiotoxin V from Taiwan cobra venom: pH-dependent conformational change and a novel membrane-binding motif identified in the three-finger loops of P-type cardiotoxin." Biochemistry 36.9 (1997): 2403-2413.